At the end of the war, squads of Jewish partisans that operated in the forests were demobilised, prisoners who survived returned from the concentration camps, and ghetto prisoners who escaped and were supported by the locals at their hiding places were freed.

Female Holocaust survivors began to create a new life based on family and children. If there was an opportunity some of them repatriated to Israel, keeping their wartime experiences secret, hiding them even from the closest family members. Testimonies of daughters and granddaughters of female survivors reveal that even silent traumatic experiences were passed down the generations, and had a negative impact on three generations.

After many years of silence, the events told and described helped the survivors of the Holocaust to come to terms with their past and overcome psychological trauma. Opening up is not easy and requires a lot of courage.

The women who shared the painful experiences solved the dilemma: Is it worth sacrificing their privacy to encourage the other women to talk about their traumatic experiences?

“There was a public library in Kaunas. […] He was probably ten years old. I didn’t tell him anything […] and, nevertheless, once he brought me the book ‘Unarmed Fighters’ by Sofija Binkienė […]. Of course, I had it, but he didn’t know. I didn’t show them […]. He said, ‘Mom, I found one book. […] And stole it … for you’. Can you imagine, I never told him anything, and he was maybe ten, but he somehow found that book, began to read it, could not put it to the side, and brought it to the mother. […] I never in my life found out that he had stolen anything. You see – you ask, how did the children react?”

Fruma Vitkinaitė-Kučinskienė

Fruma Vitkinaitė-Kučinskienė, 88-year-old former prisoner of the

Kaunas Ghetto. Her family did not survive during the liquidation of

the Kaunas Ghetto, but Fruma was saved thanks to the efforts of her

mother and local rescuers of various nationalities.

Fruma Vitkinaitė-Kučinskienė with her aunt Rivka Šmuklerytė-Ošerovičienė, 1946.

From the personal archive of Fruma Vitkinaitė-Kučinskienė

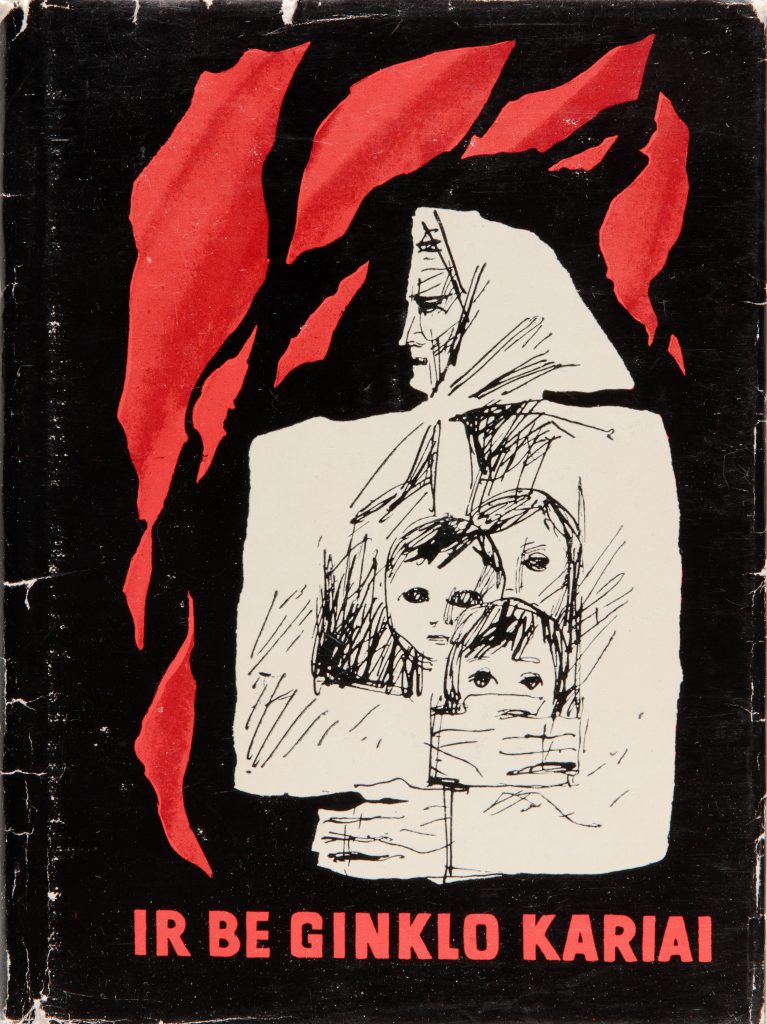

Knygos apie žydų gelbėtojus viršelis. S. Binkienė „Ir be ginklo kariai“ (Vilnius, 1967)

Tomo Kapočiaus nuotrauka

“Many who survived in the ghetto and various [concentration] camps told nothing to their loved ones. Stayed silent for a long time … couldn’t talk. And their children didn’t know what they were going through. And only in recent years many started coming to Paneriai. And they started talking. Myself to my family – also … My children were born … I started telling them from the first day.”

Fania Yocheles-Brancovskaya

Fania with her husband Michail Brancovsky after the war, in the yard of the Vilnius

Ghetto library. August or September, 1944.

From the personal archive of Fania Yocheles-Brancovskaya

Photo for the interview with Fania Yocheles-Brancovskaya in June 2018. In her hands – a photo of Fania’s family that did not survive.

Vilna Gaon Museum of Jewish History

“I was silent. I never talked about anything. […] I wanted to forget all of it. Just delete everything. […] I tried not to think about it. I didn’t write about extremely difficult situations […] there is nothing about all this. […] I wrote about completely different things. […] Enough, but not everything. Maybe it’s good that you’re asking about it because the world needs to know what it was. […] Even now, it’s hard to talk about it.”

Dita Zupovitz-Sperling

Dita Zupovitz-Sperling, 99-year-old former prisoner of the Kaunas Ghetto and the Stutthof concentration camp. Dita with her husband Yuda Zupovitz in the Kaunas Ghetto in March 1944. Yuda Zupovitz was soon arrested, tortured and killed in the Kaunas Ninth Fort.

From the personal archive of Dita Zupovitz-Sperling

Photo for the interview with Dita Zupovitz-Sperling in August 2015

Vilna Gaon Museum of Jewish History

“And after the death of my mother the Holocaust continued for me. I blamed myself [for my mother’s suicide]. Why did I get up later that day? I could have saved my mother. […] I couldn’t talk because that was the way I was taught in my childhood – do not tell anybody what’s important to you […] after my mother’s death – I wasn’t myself. I was an absolutely different person. […] I haven’t changed. A human being cannot change. I mean I forgot who I used to be. I became angry and anxious. I had no patience for anything. It all continued for too long […] we have to talk about pain, and fear. If there is no one in a family, there are no close people – then I’m ready to listen. […] My purpose is to make it easier for anyone who has a hard time … To listen. […] I talk to pupils in schools – that’s important. […] People need to know to avoid it all.”

Bella Shirin

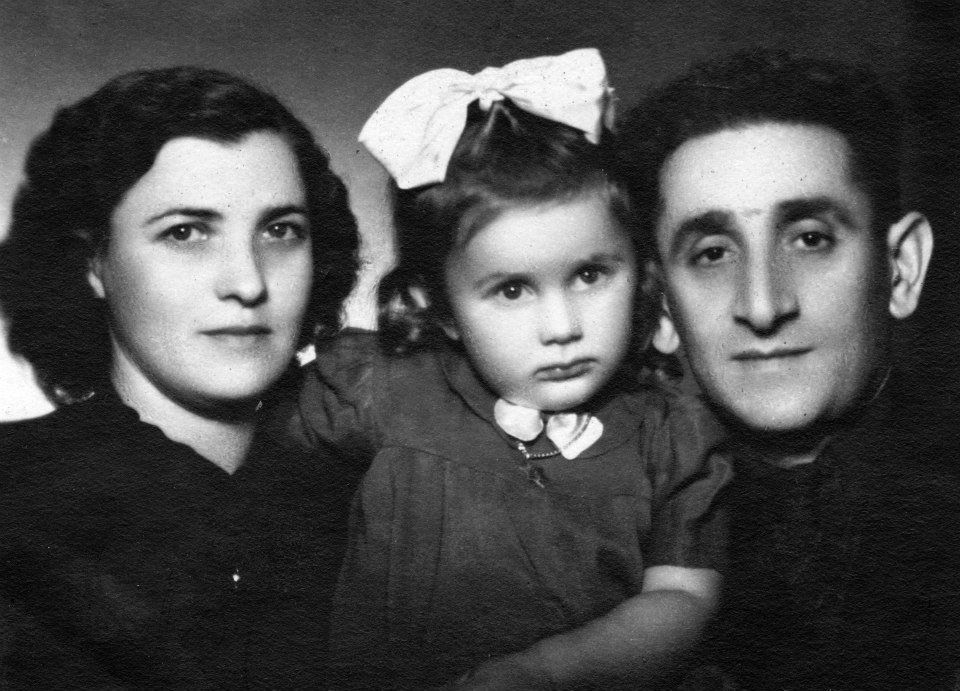

Bella Shirin, the daughter of the Holocaust survivors, with her mother and father in the 1940s.

From the personal archive of Bella Shirin

Bella Shirin, 2020. Photo by Agnė Bekeraitytė.

From the personal archive of Bella Shirin.

“I remember that in my childhood she used to say: ‘They killed my family’. I was about five years old when we went to Plungė and Kaušėnai. It was a kind of family trip, and I could not understand at that time why she was crying her eyes out. I had never seen her crying but at that time she was weeping loudly. She had such a close relationship with her mother, and she was killed in Kaušėnai. My mom was the youngest. Only her brother survived.”

Judita Gliauberzonaitė, the granddaughter of a Holocaust survivor

‘‘There was the so-called Children’s Action that day. What my eyes saw – others did not see. We were told not to leave the house, and not to open the door [but] to keep it not locked. But I didn’t manage. It was near the Neris River. The river was close … I had to see what was going on there. I dared to glance through the opened door a little … It was better that I didn’t do it … Because at that moment I saw a German SS soldier standing next to a young woman with a child. He didn’t want that child himself … They took the children away that day. She was holding her baby so he unleashed a big German dog – you know – a wolf. She was so scared – the child fell to the ground. That was the end. He took the child … Yes, I’m trying … It seems that I did not write about it. That’s why I’m trying [to tell] about it … I have to add that I’ve deleted everything I’d seen. I do not know how. It was deleted without my participation.”

Dita Zupovitz-Sperling